Materials Selection Overview

High performance composites can be considered as efficient materials, where super stiff or strong fibres are aligned with the structures loading, and so tailoring the material to the parts structural function. This anisotropy can provide massive weight saving for highly loaded applications compared to metals which inefficiently have a massive surplus of strength and stiffness in the directions with light loading. Conversely, this anisotropy and efficient tailoring results in much higher design complexity to isotropic materials such as metals which only need thickening or thinning to suit the parts loading.

A highly useful feature for allowing reasonable manufacturing cost is the ability to shape a super stiff material in a drape-able, soft form and then set it rigid by the polymer matrix hardening to create a super stiff structural part. Metals are strong and tough, but are really costly to shape, needing either powerful cutting machines, massive presses or extreme heat to melt and cast parts to the required shape.

Helping this efficient structural tailoring, continuous fibre (high-performance) composites are usually supplied in very thin sheets, so a structures thickness is easily layered to suit the local maximum loads, and hence are very efficient. Conversely, most metals use little thickness variation since they are supplied as plate, tube or rod. The cost of local thickening may allow some local plates to be welded for load introduction points, but a high level of thickness tailoring needs casting or machining which are often unsuitable for the size, shape or production rates required. So metal structures, to provide low manufacturing cost are usually weight inefficient.

As the world-wide pressure on energy use escalates, the design of weight efficient structures will become more common and the additional design and manufacturing cost for high performance composites will become more acceptable and affordable.

Fibres

The two predominant fibre types are glass and carbon.

Glass and Carbon Fibre Woven Fabric

Some other fibres are used for niche applications; quartz (aircraft radomes,) aramid (ballistic protection,) basalt (racing yacht hull,) polypropylene (impact resistant suitcase shells,) polyethylene (ballistic protection,) and PBO (Zylon) (racing car wheel tethers.)

Glass Fibre Braid Carbon Fibre Multi-axial Fabric (NCF)

Glass fibre is generally used for parts and structures where moderate stiffness, high strength, impact or creep resistance is required. Its low cost in comparison with carbon justifies its use for some stiffness critical applications such as low rate production cars, but its low modulus compared to carbon or metals generally results in increased part weight in comparison with aluminium. The best usage suiting its performance is for gas storage tanks where the combination of low cost, high impact resistance and strength provide impressive benefits over metal solutions.

Carbon fibre is used for any parts whose design is dominated by stiffness and weight which can afford its use. Its exceptional stiffness, low density, strength, impact resistance and resistance to environmental degradation are mitigated by its cost which is at least six times that of glass fibre. From the first usage in military aircraft in the 1970’s then commercial aircraft, sports goods and racing cars in the 1980’s, it is still restricted to niche applications where its cost can be overlooked to provide other user benefits.

Matrix

Matrix selection is quite straightforward. Their role is to bond the fibres to allow the transfer of load through shear by bonding and to resist the service environment,

Polyester is the lowest cost type. It withstands most environments, provides high impact resistance and can be cured at room temperature. Its downsides are its smell and curing shrinkage of around 8% which frequently causes part distortion and hence assembly tolerance difficulties.

Vinyl esters have enhanced chemical resistance and have generally better impact resistance, but have the same drawbacks.

Epoxies have no drawbacks compared to polyesters other than higher temperature and longer curing time to build the chemical crosslinking. They have much reduced curing shrinkage of around 2% providing smoother surfaces and less distortion. Their much higher strength provides very high impact resistance and exceptional resistance to cyclic loading.

Where sustained usage above 150C is required, the polymers bismaleamide (250C maximum, supersonic aircraft skins), cyanate ester (177C maximum, racing car parts close to engine heat) and polyimide (spacecraft) can be used. All of these have much higher cost than epoxies. Service temperature above 250C normally requires a change from a polymer matrix to a ceramic one allowing usage up to 3000C, the downside being much greater part fragility.

Thermoplastic materials are increasingly being used for both applications with high production rate (automotive structures) and those requiring exceptional impact (aircraft wing leading edges) or wear resistance (pump impellers and bearings.) Their ability to be re-moulded post use by chopping and pressing is a major factor driving their use in automotive structures. Polypropylene is the lowest cost form and for higher stiffness and creep resistance polyamide 6 is generally selected. Applications requiring higher sustained temperature resistance than 80C need speciality plastics such as PBT and PEEK. PEEK itself has exceptional impact and wear resistance allowing use in lubricant free bearings as well as aircraft parts.

There is a huge range of forms of fibre and resin and their combinations which have been developed to suit applications types. These are described in the manufacturing process chapter since they are generally tailored to suit a specific process set. Also presenting them is a long list would making reading rather cumbersome.

Materials selection - Manufacturing and design considerations

Manufacturing techniques for components and structures using composite materials have been developed historically to meet two very diverse and conflicting requirements; low cost production of generally large, complex shape parts for which metals are very difficult to produce, and the provision of very high stiffness and strength parts at minimum weight.

The glass fibre plastic, GRP and carbon fibre composite, CFRP manufacturing sectors have extreme differences in approach. The former generally uses poor quality, but low cost mould tooling and fast deposition of material with low pressure moulding and curing. The reasons for the use of GRP for boat hulls, wind turbine blade shells and low cost sports car bodies are simply durability from the weather and the ability to provide large, complex shape structures at low production volume at far lower cost than for metal structures. These structures are frequently lighter than if built using metals since despite having lower tensile and compressive stiffness per unit mass they have extraordinary resistance to denting and have material densities around 2/3 that of aluminium and ¼ that of steel. Applications which have their skin thickness defined by resistance to bending, twisting or buckling; which is usual, benefit from having much thicker panels than for metals and hence can be far lighter. Their manufacture using liquid resin and drape able fabrics easily allows foam cores to be included which massively increase flexural stiffness with a little additional mass.

The CFRP industry has built up primarily through the fighter aircraft and motorsport sectors, which demand careful fibre direction and thickness tailoring defined by complex stress and strain analysis. Manufacturing in this sector is defined by slow fibre deposition by skilled craftspeople or complex machinery.

Over the past two decades, a challenge of how to realise some degree of weight optimisation using fast manufacturing techniques and less costly to produce materials.

This challenge is the focus of the following chapters. The materials forms, process techniques and exemplary applications.

Applications and their design drivers

Looking at some of the well-known applications for polymer composites, we can consider what has determined the selection of the materials and process technology.

Materials performance and Applications Suitability

The issues for light-weighting through composite materials is principally affordability. The problem is two fold; materials cost and process complexity. Glass fibre is low cost (around £1.50 / kg) but does not offer high specific stiffness (E/kg.)Glass fibre reinforced structures where high stiffness is required invariably use some form of metallic structure in combination.

Low cost sports car bodies or swimming pool slides are clear examples. For these an equivalent stiffness structure could be produced using aluminium and the glass fibre is preferred where impact resistance is a main design driver.

The manufacture of carbon fibre is phenomenally energy intensive since furnaces with temperatures over 1300C are required and the material throughput rate is limited by each fibre tow (bundle of fibres) having to be carried through the furnace whilst being stretched individually and slowly oxidised and carbonised taking up to three hours in the furnace.Ref 1.The polymeric fibre feedstock, polyacylonitrile is itself very high cost; for the lowest grade suitable for the automotive sector around £18/kg.

The process complexity arises from both the additive nature of manufacturing, laying multiple thin plies of tape or cloth with each needing to be carefully conformed to a mould surface by hand or by machine and from the need to produce the material during the process. Metals and thermoplastics are formed by shaping by force or after melting; whereas most composites manufacturing processes need to create a polymer around an array of fibres. Suppliers of the former type have carried out the chemical processing themselves whereas this is most usually carried out during the composites moulding process.

From figure 2, it can be noticed that CFRP offer very high stiffness at very high cost and aluminium alloys similar stiffness at much lower cost. Aluminium alloys are the natural choice for low cost, high stiffness structures. However if the application is chasing weight saving more strongly, the lower density of CFRP provides an attractive benefit. When comparing aluminium alloy to CFRP, two benefits of CFRP must not be underestimated; damage resistance and stiffness tailorability. Aluminium alloy structures are very fragile for lightly loaded applications and hence can be highly unattractive. Two clear examples are racing car monococques and aircraft non structural panels. Until the innovative monococque designed by John Barnard and McLaren Racing in 1983 many drivers were killed racing in Formula 1. Carbon fibre monococques are much stronger and remain intact during almost all collisions. This benefit provides McLaren Automotive’s sports cars with greatly enhanced crash safety compared to equivalent aluminium structures uses by Ferrari and Porsche. Farings, fuselage skins and access panels for light aircraft are extremely vulnerable tgo impact damage, whereas GRP and CFRP structures have a much higher threshold for impact damage.

Another factor which can be highly beneficial to design is the buckling advantage provided by low density, high stiffness materials. If you look at a steel car body with its outer skin removed the shape complexity is surprising. Most panels have beading or stiffeners. A CFRP structure is much less complex and hence simpler to mould. The thin gauge material needed for steel to avoid massive weight causes design difficulty with buckling. The parts need to have their shape modfified to avoid any flat regions. CFRP at equivalent stiffness may be many times thicker and hence not vulnerable to buckling. The ability to bond lightweight sandwich materials such as honeycomb and plastic foam also has huge benefits for reducing component shape complexity.

Another major benefit for CFRP is fibre angle and thickness tailor ability. This allows a designer to preferentially align, thicken and thin fibre thickness to the applied load. This enables the often superficially marginal weight saving provided vy CFRP compared to aluminium to be greatly enhanced if the application’s loading is highly directional. This results in some applications such as automotive prop shafts and canoe oars showing massive weight savings with CFRP. This benefit is however associated with complex or slow manufacturing processes which need to lay fibres carefully in specific directions; often making the processes unsuitable for high production volumes. The manufacture of tubes or cylinders is however relatively easy and high rate; such that prop shafts, tubes and pressure vessels can be affordable.

The high fibre cost and usually slow manufacturing processes for CFRP composites restricts their application to those demanding low weight almost irrespective of cost. The high cost areas of sport, fighter aircraft, long range commercial aircraft, space and high speed machinery are all examples where manufacturing cost is a secondary consideration to lightweight.

The Challenge of Manufacturing Quality for Lightweight Structures

Unlike GRP, CFRP structures need to be manufactured with an extreme level of attention to detail, apart from their surface finish. GRP is rarely loaded to material strain close to failure and frequently has highly variable resin and sometimes void content through air introduction. Any additional resin causes local thickness increase which adds to structural rigidity. This rarely causes a cracking issue since the design strains are low and once the surface is suitably prepared and painted, the structures look fit for purpose. Utilising the unusual stiffness and strength of carbon fibre is difficult when combining the fibres with a polymeric resin. For weight critical applications, the structure should respond under loading as if the fibres are arranged as expected with the resin distributed evenly filling in the gaps between the fibres. The positive attributes of low cost, low density and low temperature curing of epoxy and other resins are negated by low stiffness, strength, temperature resistance and the susceptibility to cracking. When processed well and loaded suitably in an application, the matrix resin performs without concern, potentially for many decades longer than required. However, many things can go wrong.

TYPES of FIBRE FORM

There are three classes of material

-

Dry fabrics with resin added during the moulding process

-

Pre-impregnated fabrics – supplied ready to mould into shapes with just heat and pressure

-

Moulding compounds – thick slabs of chopped fibre, partially cured resin and fillers

These are usually with thermosetting (heat cured, cross-linking) resin, but all 3 types can use thermoplastic (melting) resins.

Generally speaking, fabric and resin is used when cost saving is a critical driver, the manufacturer has a wide range of fabric and resin suppliers to select from. Pre-pregs are used for low rate manufacturing where materials cost is not so pressing. The moulding compounds are used for high production rate applications where shape complexity is high and structural performance is quite low, since the lay up process is simple and can be automated, the tool closing force moves the fibres into the mould area.

-

Dry Fabric

Bi-axial woven fabric – (0,90 fibre 50% each) is the most common

These vary from around 100 gsm areal weight (grammes per square metre) is small tow fibre is used to over 1000gsm. Plain, satin and twill types are used

Weaving interlaces tows to form drape-able fabrics. Small (1k – 6k) tow is selected for high performance applications since the crimp (undulations) are small or for super thin (0.1mm thick layers) for super stiffness, spread tow fabrics are used where 12 k tow is spread using vibrating rollers to form a wide band. An example is Textreme by Oxeon.

Uniaxial fabrics and tapes

These confer higher laminate stiffness and strength than biaxial fabrics, but have much lower drapability and have a much slower laminating rate. However, lay up can be automated. They frequently use a thermoplastic mesh or an epoxy powder binder to hold tape together. The mesh layer allows the weaving step to be eliminated such as with Hexcel HiTape and the resultant mechanical performance is exceptionally high since there is no weaving disruption to the fibre straightness.

Multi-axial Non-Crimp Fabric – (termed multi-axial or NCF)

Carbon tows arranged straight and knitted together in 2 – 4 layer fabrics using fine thermoplastic thread to form 0.4mm - 1.0mm fabric with minimal tow crimping (undulations)

Machine development has enabled tow spreading and twist elimination to manufacture fabrics with thin (minimum 0.2mm) layers using thicker (lower cost 12k and 24k) tows

NCF Benefits

Fast machines - up to 100kg / hour – low cost

Typically 6 kg / hr for thin tow fabric

Tailored layers – bi - , tri - , quad – varying weights

Allows single axis lay - up – fabric unrolling

Thick tows ( 24, 56 typical) low-cost and can be spread and placed

Drape-able with less distortion than woven fabrics –tows slide to change area without gaps

Pre-Impregnated Fabric (pre-preg)

Combining fabrics and resins can introduce mechanical performance variability. Pre-impregnating the fabric overcomes this with a costly, but clean, attractive material type combining tapes or fabrics with a semi solid resin – prepreg. They are easy to cut, drape, lay-up complex stacks and their tackiness holds layers together.

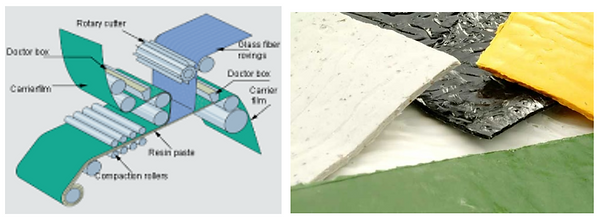

Prepreg process and machine

Unidirectional prepreg tape and woven prepreg

The two pre-preg types, unidirectional tape (UD) and woven fabric require different lay-up techniques. Woven is generally used unless extreme stiffness required. Lay up speed is around 5 times higher than tape. One difference is damage susceptibility, woven fabric laminates are quite tough since they have rough layer interfaces and hence high fracture toughness. UD tape laminates are very fragile, having smooth interfaces and hence low fracture toughness.

The different manufacturing techniques is discussed in chapter 2. Woven prepreg is suited to complex shape parts and can conform to double curvature shapes by shearing as the weave allows tows to change angle as the surface area to be covered changes. Unidirectional materials provide much higher stiffness structures since the fibres can be closely aligned to principal loads and there is no weave undulations of the tow path. However they can only conform to shapes with non-complex curvature since large pieces cannot change their coverage area without splitting or folding. Woven prepregs also allow much faster lay-up onto tool surfaces by manual techniques. Unidirectional tapes can however be laminated by a gantry or robot arm since they are plied in aligned strips rather than large floppy sheets.

Sheet Moulding Compounds

These materials were developed for high production rate, typically from 20 000 to 100 000 parts per year per mould tool. They are supplied in a similar form to prepreg as sticky sheet, between plastic films and stored in a freezer. In place of continuous fibres and low resin content, moulding compounds are a mixture of chopped short glass or carbon fibre, usually between 15 and 50mm in length with polyester, vinyl ester of epoxy resin. The PE and VE resins have fillers added to raise the viscosity and reduce overall curing shrinkage to improve surface finish. The fibres are distributed at random, but 2D orientations to provide near isotropic mechanical performance in plane. The resin is usually added to around 60-75% by volume for glass SMC and so mechanical performance is low, thereby restricting their use to non-life critical structures such as car bodies, shower trays and enclosures.

SMC Manufacture and Material

1953 GM Corvette - complete body 2010 Lotus Evora – Door skins and boot lid

House meter enclosure

For carbon SMC there are two types, one using chopped fibre tows, termed SMC and the other using chopped unidirectional prepregs. The latter type usually avoid the term SMC, using marketing names instead such as Hexcel Composites HexMc. Both types of carbon moulding compound use a higher fibre content of up to 58% (FvF) which provides much higher mechanical properties than glass SMC. The chopped prepreg types offer high strength as well as stiffness.

Their curing times are very low, around 1 minute per mm thickness which suits hot press moulding. As well as high rate curing the other main attribute is being formable to very complex shapes by simple robotic tool loading. Since the fibres are short, the pressure from the closing tool cavity forces the materials into very complex shapes and the press closing pressure usually reaches 100 Bar to allow void free precise tolerance parts to be produced without any manual intervention.

The main downside is strength variability caused by fibre flow patterns. This variability results in lower materials design allowable values, reducing the level of weight saving compared to fabric or prepreg material composite structures.